A Blog for a New Beginning

Every morning outside my bedroom window, the kookaburras shout their delight to the darkened sky. Every morning, their rowdy singing wakes me, and I smile. They celebrate before the light has come, you see. They have faith that the sun will rise.

Every evening, as I’m closing the blinds, I see the bare blossom tree outside my library. There it stands, seemingly stripped of beauty, but come spring, masses of pink flowers will burst forth like a celebration. Like a love song. Enough beauty to make you gasp. The buds sleep in the naked branches, though we can’t see them. They’ve been growing in the dark, nourished by a process we can’t see, a mystery that’s been unfolding deep in the dirt where the roots reach out.

Nature is a treasure chest of wisdom, if only we are willing to learn. There are times when her profound lessons stand out starkly. Like the last few months. The book I finished writing, The Legacy of Love, will not be published. That chapter of my life is closed. Thank you to everybody who followed along with encouragement and support over the previous couple of years. I’m so grateful.

Now, to new stories. My heart brews them all day long; each a kind of prayer, stories of love, hope, forgiveness, healing, inspiration, grace and faith. Some, I will transfer to the page, others are inside stories, so to speak. Some are lived, like my work with my sister on Ripples of Love, like the writing workshops I’m holding at the haven that is Cara House with a courageous group of children who’ve survived challenges that would make most of us crumble. Or the choir I’ve joined. Singing alongside others, I live myself into a new story, one where I’m learning, finally, that it’s ok to let my voice be heard.

Isn’t that the lesson of the kookaburras? They sing their love to the dawn, not caring if they wake the sleepers. We too are called to share our love without a care for how, or if, it’s received. What matters is the love song—and the faith that writes it.

Kookaburras raise their voices before the sun has risen, because they know a new day is coming. And so do I.

“Let the morning bring me word of your unfailing love.”

Psalm 143:8

Remembering Ebony Simpson

“Here she is. A little girl spun from gold, from her hair to her heart-shaped face to her skin and smiling eyes. She grins, happy and beloved, a precious girl, forever nine. This is where she belongs, in a unique space forged from pain and tears and a mother’s ferocious love.

Here she is, Ebony Simpson, although you can’t see her.”

These are the opening lines of a story that features in my second book, Where Spirits Dwell (2011). It is one of the last stories I wrote for that book, because whenever I’d sit down to write it, my heart would shatter.

Almost a year earlier, I’d gone with my husband to visit Christine Simpson at her home in Captain’s Flat, near Canberra. We spent an unforgettable day with Christine and her partner, the artist Günther Deix, basking in the warmth of their fireplace and arms-open hospitality. I was so grateful Christine had agreed to my request for an interview. Though how much better it would have been if I’d never heard of her at all.

The art-covered walls of the Outsider Cafe.

On August 19, 1992, Christine’s daughter, Ebony, 9, was raped and murdered on her way home from school. The appalling crime and the smiling, innocent face of the little girl taken, lodged in the national consciousness.

A box of mementos to remember Ebony Simpson in the Outsider Cafe.

Researching a book about places where spirits dwell, I came across an article about where Christine had moved in an attempt to rebuild her life. Somehow, mainly with her bare hands, she’d created a welcoming home/art gallery/cafe of breathtaking colour and beauty. I marvelled at her courage and ingenuity. And while Christine’s story was by no means a ghost story, it was a story about being haunted by love in a space she specifically created for that purpose, and that intrigued me.

Christine Simpson at her home and cafe/gallery, The Outsider Cafe.

I didn’t know that day that meeting Christine would change my life forever.

I think of her often, especially every August 19, when the chill winter wind calls to mind a mother’s pain that will never thaw. Today marks 25 years since Ebony Simpson died. In honour of Ebony, who rests beneath a rainbow of daisies, my mother had a lovely idea—plant some daisies today, to herald the coming spring and remember an angel whose spirit dwells in a toasty little cafe in Captain’s Flat. To that sweet plan, I add my own offering: a story.

EBONY IS HOME is the story I wrote about Christine and Ebony and a love that never dies, in Where Spirits Dwell. For a golden-haired girl, forever 9.

Inspiring lives

The world seems to be on its knees right now. Sorrow abounds, and a sense of futility and despair in the face of so much human suffering. I understand. Seeing the images of stricken children in Syria last week undid me, along with most people. Apart from the practical ways we can help (I donate to Oxfam every month, some amazing Facebook friends are on the frontline with refugees), we each must find our own way to process these events. As always, I find hope in stories, in particular, the stories of individuals who’ve endured deepest pain with compassion intact—they’ve borne witness without closing their hearts, even though in many cases, tragically, they did not survive the persecution they recorded.

I believe these illumined souls carry a piece of the puzzle that will heal the world. The gifted Etty Hillesum was one. A Jewish woman living in Amsterdam, she poured her soul into eight diaries between 1941-42, documenting how her world darkened as Nazi oppression spread into Holland. In one entry, after a Gestapo officer threatened her, she wrote, “I am not easily frightened. Not because I am brave but because I know that I am dealing with human beings and that I must try as hard as I can to understand everything that anyone ever does … I felt no indignation, rather a real compassion, and would have liked to ask: ‘Did you have a very unhappy childhood, has your girlfriend let you down?’”

On July 1, 1942, she recorded a kind of prophetic vision: “I am in Poland every day, on the battlefields, if that’s what one can call them. I often see visions of poisonous green smoke; I am with the hungry, with the ill-treated and the dying, every day, but I am also with the jasmine and with that piece of sky beyond my window; there is room for everything in a single life.”

Bearing witness: Etty Hillesum

When a roundup of Jews took place, Etty volunteered to go with them to the work camp, Westerbork, the last stop before Auschwitz. Etty, who had certain privileges, could move freely between the camp and Amsterdam, so she transported letters and medicine to and fro, ignoring many possibilities for escape. Finally transported to Auschwitz with her brother and parents, she is said to have thrown a postcard from the window that said, “We have left the camp singing.”

Etty was 29 when she died at Auschwitz less than three months later—her family also perished. What strikes me is that, somehow, her inner light was never dimmed. “I know about the mounting human suffering. I know the persecution and oppression and despotism and the impotent fury and the terrible sadism. I know it all,” she wrote in her diary. “And yet—at unguarded moments, when left to myself, I suddenly lie against the naked breast of life and her arms round me are so gentle and so protective … That is my attitude to life and I believe that neither war nor any other senseless human atrocity will ever be able to change it.”

My prayer is that more of us—all of us—learn to live as instruments of peace. Such is how we can contribute. “We should be willing,” as Etty wrote in her final diary entry, “to act as a balm for all wounds.”

Sources:

https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/hillesum-etty

Sacred Journeys: A Woman’s Book of Daily Prayer, by Jan L. Richardson (Upper Room Books, 1995).

Traveller in time?

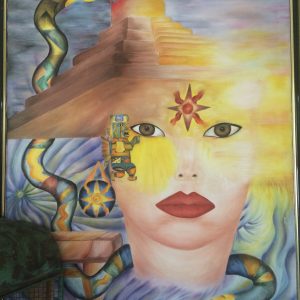

Relaxing in a blue velour armchair in a dimly lit room in 2002, lawyer Steve* was about to meet his bloody end—as it had taken place almost 1900 years before. In the midst of past life hypnotherapy, the married father-of-two had seemingly uncovered a previous existence as a commanding Roman legionnaire. “We were in a canvas tent discussing the battle-plan. Everything was under control. There was the clinking of swordplay outside as the men sharpened their skills,” he recalls. “I felt upbeat, excited and confident.”

While Steve remains unsure of what to make of his experience, this much is certain: the memory of what happened next has forever changed the course of his present life. At the hypnotherapist’s prompting, he projected forward some days to the battle, but was unprepared for the “incredibly powerful feelings” that consumed him. “I was totally gutted, perhaps in both senses of the word. There were thousands killed—friends, loyal followers, youngsters. It was all my fault. I could barely speak. My eyes were red and wet with tears,” he says. “The feeling of personal responsibility and guilt for leading the men into a massacre was unbearable. The weight of despair is impossible to convey.”

The year, as Steve saw it during the regression, was 111 AD, yet the misery in his words is as palpable as if he were mourning last week’s loss. Whatever forces were at work when Steve took his journey in the Jason recliner, the topic of past lives has enthralled Westerners at least since 1952’s (since debunked) case of a Colorado woman who recalled meticulous details of living as a 19th century Irishwoman named Bridey Murphy. On the net, you’d need a whole separate life just to explore all the websites the subject has spawned. If you’re game, $14.95 is the price to download software that purports to unearth your past lives—one brief credit card transaction, and the rest is history.

Or is it? Whether the memory is true or not is irrelevant, according to Melbourne hypnotherapist Dr. Frank Jockel, PHD. Anxiety, physical pain, fears and phobias, he claims, can melt away with the recollection of a past life. “People look to past life therapy because they feel stuck in a rut, they’ve been to psychiatrists, psychologists, clairvoyants and fortune tellers searching for an answer,” says Jockel. “A client who’s a doctor had a pain in his neck that had been there for a quite a while. During past life therapy, he saw himself being chased by a mob and someone threw a stone and it hit him in the neck. Ask the question ‘Did it actually happen?’ Who knows? But has the pain in the neck gone? Yes.”

Would this work for me? I don’t have a pain in the neck to contend with, but what plagues me—an obsession with King Henry VIII and his six wives—certainly might feel like that to my Tudor-tired family and friends. One glimpse of historian David Starkey on the TV and the blood drains from my husband’s face and he flees, shrieking down the corridor like the ghost of Henry’s fifth wife, Catherine Howard, is said to do. Starkey’s bricklike Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII commands my bedside table, and in the kitchen, my trusty Music From the Reign of Henry VIII cassette (yes, cassette) means a volté at breakfast time is never out of the question. Not even a 750-piece puzzle depicting all of Henry’s hounded ladies is beneath me.

Could this fascination endure because I once walked among them? The idea has accompanied me since childhood, and now, with the image of myself in rustling damask reignited, it was time to finally see if I’d lived before.

“Anne Boleyn” dances outside Hever Castle, ancestral home of the doomed queen, in 2014.

First stop was Sydney psychic Kate Barnes. The willowy strawberry-blonde who claims to have channelled Michael Hutchence for Australian Style magazine, describes herself as a medium, healer and clairvoyant—the latter, she explains, means “sight with your eyes” so she’ll view my former selves projected like a film before her open eyes. “I’m looking at a jungle environment,” she declares in her thick-as-the-bush Aussie drawl. “I’ve got a feeling I’m in South America.” It’s an ancient civilisation, probably Incan, and I’m unsettled by her vision that I’ve “had one child torn away” from me for child sacrifice. That heartbreak is likely to make me an over-vigilant mother today, Kate advises, and I’m eager for her to leave that life behind.

My Year 12 major artwork. Why does it feature an Incan pyramid?

“You’ve been a singer!” she suddenly announces, “I can hear this ooaaahh. It’s very operatic: oooahhh.” As she outlines my glamorous life in late 1800s France or England as a “statuesque” chanteuse with a generous cleavage, I’m reminded of my enthusiastic warbling at karaoke—minus the gowns and “many male suitors” that I was formerly accustomed to. As our 90 minute session progresses, I learn that I’ve belly danced in the Middle East, been a courtier at the Palace of Versailles, a jolly 17th century pirate on the Caribbean seas whose ship was swamped by a massive wave (huge waves are my recurring nightmare) and a revolutionary French poet/journalist by the name of Charles Monseurrat. Kate senses that many of the people around me were guillotined in Charles’s lifetime, and I can’t help but remember the red birthmark at the back of the neck that myself, my mother, sister and daughter all share. Chillingly, Kate also met the spirit of my late Godfather. I tensed at her spot-on descriptions of his distinctive gestures, appearance, and her perception of how he died. But where—I had to inquire, when Kate wonders if there’s something she hasn’t “picked up on?”—was my Tudor life?

Is a swashbuckling past behind my passion for the sea?

For as much as I was enjoying her recounting of some of my 600 (!) costume changes—it’s like the MGM wardrobe department has flung open its doors to you for a personal frock-up—when my moment arrived, it was bittersweet. “I can see a removal of collar for a beheading,” says Kate, delicately miming the gesture. If I hadn’t been Anne Boleyn herself—his famous second wife, whom Henry sent to the block on trumped-up adultery charges—I’d been her lady-in-waiting, she states. These words should have made my blood run cold, but coming as a postscript, it was just like chancing upon a beloved, long-dead relative in a well-worn photo album.

Before leaving, I ask if there is any past life explanation for my current fear of driving. In a heartbeat, Kate sees me steering a red-cross ambulance and dodging bombs in some war-ravaged city. This is exhilarating but doesn’t go far towards explaining my terror. When I mention the scene to my mother her dry response is, “I don’t see you driving an ambulance in this life, a past life or a future life.”

Instead, I steered myself towards kinesiology. Energy kinesiology works on the principle that “muscle testing” can identify imbalances in different structures of the body. The practitioner asks a yes/no question and the resistance of your muscle, usually a forearm, provides the answer. This is a novel method of accessing past lives and I can’t imagine what awaits me at the southern Sydney apartment of kinesiologist Sherry Mead. A gargantuan dream catcher dominates most of a wall, and I wonder what lives we’ll net today.

Answering that proved complicated , but warm-natured Sherry showed cool efficiency in keeping track of the interminable folders, information sheets and lists she had to consult in tracking my past lives. “Muscle testing is our tool to follow the path or to find the story,” she explains. Via what is essentially the method of elimination, Sherry established that I’d been a swordsman in the Spanish royal court in 1521 (right year, wrong country) and a 9-year-old Greek girl in 1013. I thanked Sherry, but more than ever; I was drawn to the bright light of hypnosis.

Hypnotherapy is the quintessential past-life experience, as Steve discovered. “I had been pretty risk averse in my life and reluctant to push myself forward and stand-out from the group,” he says. “The Roman legionnaire experience certainly showed why I might have retreated into a shell. Soon after this experience, I felt that perhaps there was a reason for my ‘blockage’ and it was okay to move on and start asserting myself.” He soon grasped a new professional opportunity and moved interstate with his family. “There is a new energy, excitement and happiness. Now I stand up for what I think is right.”

That’s settled then: I will go under. Imagining my ancient self skipping down velvet English hills, I make an appointment with Sydney hypnotherapist Marlaine Nicholson-Smith.

“Hypnosis is like the dream state but awake,” Scottish-born Marlaine informs me during our pre-session chat. “I have to quieten the conscious mind to access the subconscious. The memories are there within you but a lot of us don’t want to remember, or don’t now how to remember.” For the first few moments in the recliner’s plush embrace, as Marlaine’s hushed voice instructs me to feel “heavy as lead”, I’m remembering only that I’ve left my mobile phone switched on in the next room.

The pesky thought eventually recedes during the guided meditation, where I’m to imagine myself walking down a golden path, inhaling a rainbow of multi-hued “mists.” Soon, I’m plunged into a swirling spiral and when I emerge at the other side, I’m supposedly inside a past life. Then—nothing. But pictures do emerge as, ever so slowly, I lose awareness of where I am, and start to completely inhabit the landscape in my mind. Still, when I listen back to a recording of the session, my answers remain mostly monosyllabic and the vivid detail reminiscent of the most intriguing past life recollections I’ve read about is absent.

During hypnosis, I’m advised to “inhale” a rainbow of multicoloured mists.

I “see” a barefoot young woman with long dark hair, and an empty stone cottage, but there’s no one around—it’s like a ghost town. When I’m asked for the date, there is a long pause before my clipped “1500s”—of course I’d say that, in my hope. Yet, propelled to the day I departed this mundane life, a tear stung my eye as I watched this girl whose features were never clear die in her childbed. Marlaine later assured me that memories are often hazy: “Often, you don’t get a proper picture, you just get a feeling that something’s there.”

The second life I recounted—intended to pinpoint the origins of my fear of driving—flowed better. This time I’m a stable boy of 15 in the days of Roman chariots. He’s as happy as Larius until the day his master invites him to take the reins, for a lark, and the horse and chariot veer wildly out of control, throwing the youth and condemning him to be reborn centuries later as a bus-bound writer with a thing for strappy shoes that lace around the ankle. To curtail my fear, Marlaine suggests that I reimagine the event with a happy ending, then “One: feeling your body return to normal. Two: feeling your spine against the chair, and three: wide awake and refreshed.” I snap my eyes open and drag my tingly, leaden limbs from the chair, thinking all the while that it would have been fun to continue for just one more life…

What? More Romans?! A chariot accident may explain my fear of driving…

Barry Williams, the editor of The Skeptic, the journal of the Australian Skeptics association, soon bursts my bubble: “Self delusion is one of the strongest attributes that all human beings have,” he cheerfully tells me. While he immediately poo-poos the psychic reading—“she was never going to tell you that you were a common rag picker who spent most of his time with his finger up his nose”—and my brush with kinesiology–“one of the looniest things people have come to believe”—hypnosis makes him pause for breath. “It is on the fringes of science … the hypnotist is giving you permission to behave how you wouldn’t normally behave, make a fool of yourself if you like.” (Here, I chose to remember the celebrities who cross-dress for TV hypnosis specials, rather than my own purposeful utterings about a crashed chariot.) “You want this to be true,” he sums up. “It’s the same as when people see pictures in clouds.”

But that’s not so bad, is it? Bombarding my vague and pregnant sister with tales of my spiritual quest recently, she surprised me with a decisive: “You know what you were. You don’t need to ask anyone.” Perhaps, I thought, sinking into the couch with my latest guilty pleasure—Robin Maxwell’s The Secret Diary of Anne Boleyn—you could have told me that earlier.

* Not his real name

No answers: the mystery of my fascination with Anne Boleyn remains. (Image Hevercastle.co.uk).

Author’s note: I was commissioned to write this article for a Sunday supplement more than a decade ago, but it was never published. My sister suggested I post it, so here it is, a little dated in parts, but hopefully still of value. Something that’s definitely changed since I wrote this is I now believe more in the idea of “simultaneous” lives, rather than “past” lives … more on that later!

Heal With Your Pen

The words came to me in a meditation. I wrote them down: HEAL WITH YOUR PEN. Since that morning, almost a year ago, I have come to understand so much more about what those four words signify.

Heal with your pen. At first I thought that was a pointer for my own life, that I would heal myself by writing my story, that I would evolve—progress on the spiritual path and thus “heal”—through sharing my experiences, be it in books, blog posts or on social media. Yes, I thought, that feels right.

I have always understood the healing power of stories.

But there was more, I realised, as I began to meet women who have extraordinary life stories they are bursting to explore. I say “bursting” because of the readiness with which they shared their life journeys with me. In a way, we seem magnetised to each other. What an honour. One of these women, Lisa, has become a dear friend (a true Spirit Sister rediscovered!) and I am honoured to be writing her biography this year. What a task, what a joy, what a story.

“Spirit sis” Lisa is on the left.

All the women I’ve met share this in common: I marvel—marvel and bow down—at what they have endured, and how they have emerged on the other side, as teachers of love and grace and resilience. Meeting such women made me wonder; Am I to use my pen to serve them? Will I write, edit or publish their stories? All three perhaps? Me, a publisher?! I don’t feel like anything is impossible with spirit at the helm.

Lately, something else has become apparent. I am being drawn to HEAL WITH MY PEN by encouraging others to do the same. In this scenario, my pen will offer tips and pointers to help people heal themselves by freeing their stories. For example, later this year, I have been asked to talk about writing and storytelling to children who’ve suffered trauma. I am thrilled to do so.

I have also been sharing my story verbally at a couple of talks. So to heal with my pen has permutations, as I am discovering. Thinking of stories, and of the healing power of sharing them, reminds me of something I read the other day. There are myriad names for that universal force that connects us all: many call it God, others call it the Universe, some describe it as Divine Intelligence, in scientific circles, it is “the field,” in Aboriginal culture it is “the Dreaming” and in certain Native American traditions it is the Great Spirit. Ultimately though, all the names can only point to that unfathomable vastness that cannot be contained by any name, as the Tao te Ching teaches: “The name that can be named is not the eternal name.” I accept that, and yet I love this description I came across in an old prayer:

God—that is, that which goes by many names and none—is “the author of love.” And love, of course, is the ultimate story that heals.

Beautiful graphic by KSH Creative.